Dehydroepiandrosterone and Addiction

Yadid Gal, Ph.D.

The Mina and Everard Goodman Faculty of Life Sciences, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan 5290002, Israel & The Leslie and Susan Gonda (Goldschmied) Multidisciplinary Brain Research Center, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan 5290002, Israel.

Introduction

Drug addiction has a great influence on society. In the United States alone, the annual societal cost of substance use disorders (SUDs) amounts to about $740 billion in medical care spending and productivity losses, and SUDs are listed among the top ten non-genetic causes of death globally (McCollister et al., 2017). Drug addiction is also a growing social and psychological problem (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US) & Office of the Surgeon General (US), 2016; Buchanan, 2006). For many years, society considered drug addicts to be people with weak willpower. It was widely thought that addicts could choose to stop using drugs if only they had some self-control and principles. Nowadays, science has changed this view, defining drug addiction as a complex brain disease that affects behavior in many ways, both biological and environmental.

Addiction and DHEA

DHEA is a steroid produced in the gonads and in the adrenal gland. In addition it is produced in the brain and acts as a neurotransmitter, hence, it can be defined as a ‘neurosteroid’ (Shah, Chin, Schmidt, & Soma, 2011). DHEA is currently used in Western countries as a food supplement. It has anti-aging and antidepressant properties, and contributes to increasing motivation and a general well-being (Huerta-García, Montiél-Dávalos, Alfaro-Moreno, Gutiérrez-Iglesias, & López-Marure, 2013). Studies indicate that DHEA administration improves memory and cognitive processing (Huerta-García et al., 2013), induces neurogenesis and neural survival, and attenuates levels of the stress hormone cortisol (L.Ulmann,J.-L.Rodeau,L.Danoux,J.-L.Contet-Audonneau,G.Pauly, 2009; Yadid, Sudai, Maayan, Gispan, & Weizman, 2010). In healthy men and women, DHEA has been shown to induce relaxation and a higher capability of handling stressful situations (L.Ulmann,J.-L.Rodeau,L.Danoux,J.-L.Contet- Audonneau,G.Pauly, 2009).

In a research monograph written by Wilkins et al. at the end of the previous millennium (Wilkins et. al., 1996), the authors suggested that plasma levels of DHEA sulfate (DHEAS) may be used to discriminate between treatment outcomes in groups of cocaine addicts (Harris, L.S. et. al Ed. & College, 1996). They found that those who had high basal levels of DHEAS remained abstinent following treatment for cocaine dependence/detoxification. Later, Buydens-Branchey et al. compared levels of cortisol and DHEA in cocaine addicts during abstinence (Buydens-Branchey, Branchey, Hudson, & Dorota Majewska, 2002). They demonstrated that levels of cortisol were highest on day 6 of abstinence and then subsequently decreased. DHEAS levels were low on day 6 and highest on day 18 of abstinence. Analyses revealed a significant effect of frequency of use of the drug. More sustained cocaine use was associated with higher cortisol levels and less pronounced cortisol decline after discontinuation of cocaine use, but drug intake variables had no influence on DHEAS levels. During cocaine abstinence, cortisol levels declined more noticeably whereas DHEAS/cortisol ratios rose more dramatically in aggressive versus non-aggressive addicts. Other studies (Wilkins et al., 2005) identified each of the patient outcome groups by levels of circulating DHEAS and distressed mood at treatment entry. Results showed that cocaine addicts with high circulatory DHEAS levels relapsed less to cocaine abuse after 3 weeks of non-pharmacological treatment, during a 6-month follow-up. The authors suggested that in abstaining patients, distressed mood during withdrawal may have been mitigated through antidepressant-like actions of enhanced endogenous DHEAS activity (Brzoza et al., 2008; Genud et al., 2009; Wolkowitz, O.M., Reus, 2003), thus contributing to continuing abstinence and treatment retention. Patients with high levels of distressed mood at treatment entry and low DHEAS levels may express higher susceptibility to leaving the rehabilitation or may more easily relapse. Hence, correlation between endogenous DHEA levels and treatment outcome of addicts suggests the possibility that patients may benefit from adjunctive pharmacotherapy with DHEA.

A new horizon: Screening for potential treatments

An immediate need for anti-addictive treatment

Problem of addiction to substances is still unanswered by the pharmaceutical industry. Treatment of the urge to use drugs and relapse is considered extremely difficult, especially with regard to cocaine and opiates, which are highly dangerous and aggressive drugs of abuse. For over 30 years, no effective remedy has been found nor has any innovative treatment been offered to addicts. So far, treatment options offered were mainly psychological, provided in therapeutic centers. The only pharmacological treatment currently availbale around the world is controlled, clinical administration of substitute drugs. In other words, the common therapeutic approach is detoxification followed by treatment with an alternative substance that replaces the addictive substance, such as Subutex and Adolan (Tomkins & Sellers, 2001). However, the addict may and usually develop dependence to this replacement. A safer, but longer rehabilitation program uses psychological and behavioral treatment in an enriched environment provided in various therapeutic communities such as rehabilitation centers (McLellan & Weisner, 1996).

DHEA treatment for substances of abuse

Effect of DHEA treatment on acquisition of substance dependence

In a study investigating the influence of high levels of DHEA in the brain on the acquisition of cocaine intake in rats, we first showed that DHEA pretreatment combined with concomitant use cocaine, attenuated cocaine-seeking behavior and elevated the levels of dopamine and serotonin in several brain regions relevant to cocaine addiction (Maayan et al., 2006). Chronic cocaine self-administration induced elevations in brain DHEA, its sulfate ester, DHEA-S, and pregnenolone. The study revealed that increased levels of DHEA in the brain following cocaine selfadministration may serve as a compensatory protective mechanism geared to attenuating the craving for cocaine. Such anti-craving effect may be further enhanced by DHEA treatment before and during cocaine self-administration, and is characterized by normalization of DHEA levels in the brain (Maayan et al., 2006). In one of the studies (Maayan et al., 2006), rats initiated cocaine self- administration already with high basal DHEA levels in both peripheral system and the brain., This effect had been achieved due to pretreatment followed by continuous concomitant treatment with DHEA, which prevented drug consumption and drug seeking (see Fig 2) behavior. Thus, it was assumed that timing was a crucial factor in the anti-craving effect of DHEA. It was further concluded, that subjects with high basal DHEA levels may be less prone to developing dependency and tolerance to substances and thus, to relapse.. This observation is also supported by Reddy and Kulkarni (1997a,b) who show that DHEA treatment prevents the development of tolerance to benzodiazepines (BZ) in mice. In addition, DHEAS treatment prevents the development of morphine tolerance and attenuates abstinent behavior in mice (D. S. Reddy & Kulkarni, 1997; Doodipala S. Reddy & Kulkarni, 1997; Ren, Noda, Mamiya, Nagai, & Nabeshima, 2004).

Effect of DHEA treatment on maintenance of drug-seeking behavior

It has been successfully shown that chronic exposure to exogenous DHEA (2 mg/kg) attenuates cocaine self-administration and cocaine-seeking behavior inrats to <20% of their maintenance levels (Doron, Fridman, Gispan-Herman, et al., 2006) ; see Fig 2). No surge in active lever response accompanied initiation of DHEA treatment, which would have been expected if DHEA blocked the reward effect of cocaine. This result is interesting, since it is most difficultaddicts to stay on an anti-drug program during the first weeks of detoxification, when expectation for reward is highest (Self and Choi, 2004). Indeed, when higher doses of DHEA (10–20 mg/kg) were co-administered with cocaine for a short period of time (4 days), a markedly increased cocaine-induced Conditioned Place Preference (CPP) was reported (Romieu et al., 2003). Extinction of responding maintained by appetitive rewards has been suggested to induce multiple stress events including activation of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis, glucocorticoid secretion, and central β- endorphin release (Shaham, Shalev, Lu, De Wit, & Stewart, 2003; Vescovi, Coiro, Volpi, & Passeri, 1992). Hence, it was suggested that alleviation of distress associated with cocaine withdrawal may facilitate achieving abstinence (Self & Choi, 2004; Wilkins et al., 2005). Furthermore, during withdrawal, cocaine addicts are found to have high plasma cortisol levels, which are at their highest at 6 days after initiation of the withdrawal and then gradually decrease (Buydens-Branchey et al., 2002). As the levels of plasma cortisol decrease, the levels of DHEAS gradually increase. Only patients who had spontaneous increase in DHEAS levels were identified as being successful at abstaining from cocaine usage over time (Wilkins et al., 2005). The study conducted by Wilkins et. al. in 2005 suggested that there was a direct connection between DHEA/DHEAS, low distressed mood levels, and changes in CNS salience during withdrawal.(Wilkins et al., 2005). Another study supported this hypothesis and further proposed that appropriate individual DHEA dosage was critical for the prevention of relapse (Shoptaw S, Majewska MD, Wilkins J, Twitchell G, Yang X, 2004). The effect of exogenously applied DHEA (2 mg/kg) on cocaine-seeking behavior may possibly be explained by the natural conversion of DHEA to DHEAS found both in the the serum and the brain (Maayan et al., 2005, 2006) in addition to increased levels of other bioactive neurosteroids (Dubrovsky, 2005). These neurosteroids may interact with various neurosystems involved in mood and drug-seeking behaviors, such as glutamatergic, GABAergic and dopaminergic systems. Since DHEA can function as an antidepressant in both animals and humans (Maayan et al., 2005, 2006; O M Wolkowitz et al., 1997), it may lower the depression/distress involved with cocaine withdrawal (Self & Choi, 2004), similar to the β-endorphin-induced lowering of frustration during extinction (Roth-Deri et al., 2003b, 2004).

Effect of DHEA on extinction of drug-seeking behaviors

In order to learn more about the effect of DHEA on the extinction phase after cocaine self-administration, an experiment was conducted in which two groups of rats were trained to self-administer cocaine until stable maintenance levels were attained. Following that, cocaine maintenance was terminated and assessment of the developed craving to the drug was performed. The conditions during the extinction phase were the same as during training with an exception that the cocaine syringes were removed, and that rats were injected DHEA (2 mg/kg i.p.) or saline as a vehicle (same volume) 90 min prior to placement in the operant chambers. The results showed (Fig 1) that saline-treated rats pressed on the active lever significantly more on the first day of the extinction phase as compared to those which were injected DHEA. Moreover, DHEAtreated rats returned to their baseline starting from day 2 of the extinction period,, whereas salinetreated rats never returned to baseline behavior. The most significant and important effect of DHEA treatment during drug washout was observed in the long term. After a total of 34 days since the last exposure to cocaine (27 days from the end of treatment), rats received a priming injection of cocaine before being placed in the self-administration chambers. Active lever responses, reinforcements, and inactive lever responses were recorded. In the relapse test, number of active lever responses was significantly lower in the DHEA-treated group compared to salinetreated group (Fig 1).

Effect of DHEA treatment on reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior

There has been only a few studies published on neuroactive steroids and their role in reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior.(Nie & Janak, 2003; Anker, Holtz, Zlebnik, & Carroll, 2009). We examined the effect of DHEA on cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug seeking in rats exposed to withdrawal conditions. Rats which received DHEA (2 mg/kg) daily showed minimal response to acute priming with cocaine. Our studies led us to the conclusion that DHEA can protect against relapse in substance addicts. This hypothesis have been described in another research in 2006.(Doron, Fridman, Gispan-Herman, et al., 2006).

DHEA treatment Decision Support System

From the abovementioned observations, researches and convergent data it appears that:

- Selecting correct DHEA dose is critical for obtaining beneficial effect on rehabilitation

- Correct intensity (starting point and duration of treatment up to a ‘stop signal’) is crucial for gaining optimal treatment results

- The treatment needs to be provided preferably in therapeutic centers where enrichment environment is available, (rather than during detoxification)

Based onthe above mentioneddeveloped optimal addiction- treatment- supporting- system which incorporate the following unique features :

- Elicited system. The initial baseline level of DHEA in blood is less important than DHEA spillover and the response to DHEA systemic intake(see E below). Responders, and possible treatment success

- Dynamic response. Addicts’ response to DHEA is important and measured by (i). The individual degree of change of the initial baseline, (ii)the extent of the dynamic rate of normalization (allostasis) of the normal population

- Tailored treatment. Certain patients may be identified as “Non-Responders” when tested at the end of the first month of the treatment (“early prediction”). These patients will be given an adjusted dose for another month. “Responders” will stop treatment – after one month. Both groups will be monitored and evaluated (see E) up to three months. The treatment may be ultimately terminated after 3 months. Certain patients that showed partial response (as to our algorithm output) may continue the treatment at a lower dose for additional 3 months (6 months total treatment) “Non-Responders” will be offered an opportunity to continue with other treatments in our Basket).

- Stop signal. It is crucial to stop the treatment when patient is stabilized (a stop signal derived by the algorithm) E. Complex data (specific value). The monitoring of the patients will be based on 6 parameters, described below. Each of these parameters is given a certain weight and its value, (the percent of its’ valuable effect in the complex “puzzle” of the response to the treatment) is calculated by the ‘Algorithm’.

The Algorithm

We estimated Algorithm probability to predict abstinence as 80% (at 6 months from the end of the treatment) from measures at one month of treatment with DHEA.

From our experience (running 4 trials, one in a detox center and 3 in therapeutic centers) we identified/selected few parameters (based on neurochemical cognitive and medical evaluations). We currently have 4 parameters and 7 measures.

DHEA and DHEA-S

The levels of DHEA and DHEA-S as well as their ratio DHEA-S/DHEA are arranged in identified specific “blocks”, at start of the treatment point (baseline)and at the end of the treatment point.

The rate of change between these two blocks allows us to predict probability of abstinence at 6 months post treatment. This prediction (80%) is available only after triggering the neurological system of the addict by applying DHEA at different doses. We add to the algorithm 5 values (DHEA, DHEAs, DHEAs/DHEA, ranges of various block combinations) and behavioral, cognitive and clinical measures.

DHEA in clinical trials

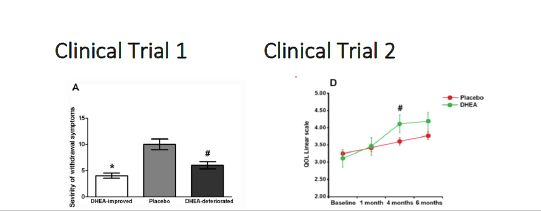

3.1 Using DHEA as a treatment for addiction in poly-drug users Clinical Trial No. I.

Clinical trials inclusion criteria: age 18+, men, current DSM IV diagnosis of opioid dependence (Heroin addicts). 56 placebo and 58 DHEA; DHEA 100mg/day during 3 w detox. Phase Buprenorphine 6-10 1st day, 8-12 2nd and then decreased 1-2 / day. Tests: Hamilton Psychiatric Scale of Depression )HDRS), Hamilton Psychiatric Scale of anxiety (HARS), Withdrawal Symptoms Questionnaire (O’Conor &Kosten).

We reported (Maayan et al. 2008) that providing DHEA to poly-drug addicts as an add-on compound to their routine medication protocol was mostly effective (65% of treated subjects) in patients who had not previously used either cocaine or benzodiazepines and who had experienced only a few withdrawal programs (Maayan et al., 2008;). Nonetheless, 35% were deteriorated on anxiety and depression scales. It is worth to note, that both sub- groups showed improve in withdrawal symptoms. Hence, we concluded that DHEA will benefit in enrichment environment e.g. therapeutic centers, see below).

Clinical trial II : Effect of DHEA add-on therapy on rehabilitation of polydrug users.

In view of these previous clinical and preclinical findings, whether DHEA will prove to have efficacy as an adjunctive treatment in drug users must be further examined. Consequently, our laboratory proposed a double-blind, placebo-controlled study to test the long-term effect of DHEA on addiction indices, that succeeded to improve decision-making and lower relapse rates significantly (Ohana et al., 2016;). As mentioned above, levels of DHEA and DHEA sulfate (DHEA-S) were found to decrease during abstinence in human drug addicts (Buydens-Branchey et al., 2002; Wilkins et al., 2005), and this decrease was found to predict later drug reuse (Wilkins et al. 2005). This has led to the suggestion that increased circulating DHEA-S levels may enhance brain resiliency during withdrawal by lowering the distressed mood levels of addicts (Doron, Fridman, Gispan-Herman, et al., 2006; Doron, Fridman, & Yadid, 2006; Wilkins et al., 2005). In research conducted by our laboratory (Ohana et al.), 120 patients were interviewed; Participants: Retorno & Malkishua; Baseline: 72 (38/34); 1 month: 64 (34/30); 4 months: 49 (29/20); 6 months: 26 (15/11); Placebo: 29 m. & 9 f; DHEA: 27 m. & 7 f. 85% reported using multiple drugs on a weekly basis 94% cannabis 50% stimulants 47% heroin On average, they started abusing drugs at age 16. The initial evaluation meeting with the participants consisted of two sessions in which they provided demographic details, performed psychological tests and gave blood samples. In addition, further assessments involving psychological testing and blood samples were collected after 1, 4.5 and 6 months (study termination). We found that DHEA treatment resulted in an increase in DHEA-S 1 month following treatment, and the level of DHEA-S predicted relapse in the follow-up assessment. Additionally, based on the PANAS scale, DHEA appears to decrease negative effect during treatment. Importantly, in a 16- month follow-up, the reuse rates in the DHEA condition were about a third as compared to placebo. It appears that these results emphasize potential relevance of findings in animal studies of DHEA to recovery following addiction of human addicts. The current findings offer early confirmation of the potential long-term beneficial effect of DHEA on drug reuse.

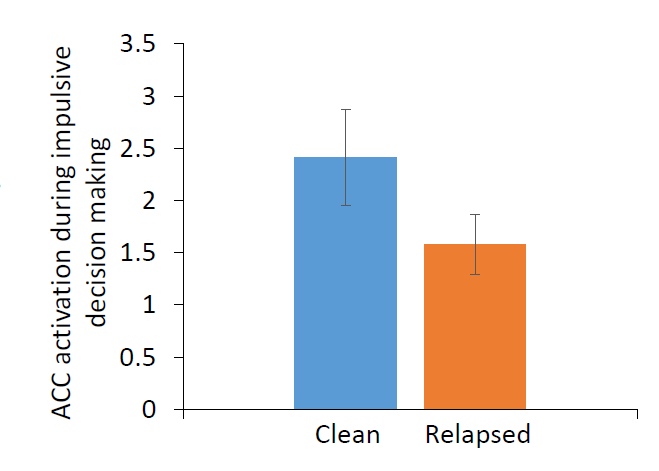

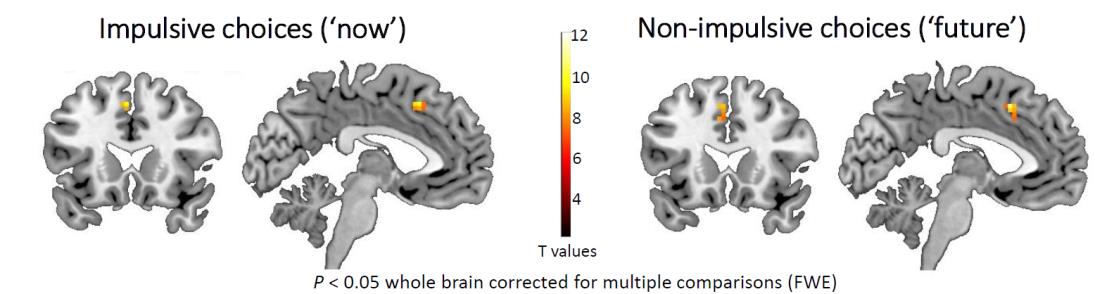

Clinical Trial III: Imaging the cognitive outcome of DHEA treatment on decision making

A prominent feature among drug addicts is impulsive decision making. Impulsivity is both a risk factor for drug addiction and a process affected by drug abuse. Drug addicts consistently show elevated impulsive behavior as compared to healthy controls, depicting their preferences for an immediate reward (consuming a drug) over larger delayed rewards (improving health, financial stability, etc.). The decision making definitely contributes to drug abuse initiation, maintenance, and relapse. fMRI studies revealed elevated sub-cortical (“impulsive system”) and blunted prefrontal cortex (“executive system”) activation in drug addicts compared to healthy controls during impulsive decision making. To date there has been no study which assessed whether neural and behavioral markers of impulsivity could predict long-term relapse risk.

Delay discounting (DD) task is a well-established behavioral probe for impulsive decision making, assessing the tendency to choose smaller immediate monetary rewards over larger delayed rewards.

Study Design: Multi-drug withdrawn patients are recruited at Retorno rehabilitation center based on strict inclusion/exclusion criteria. Eligible participants complete: 1. The DD task during a behavioral experimental session within one week of their submission to Retorno rehabilitation program. 2. The DD task during an fMRI scan session at Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center approximately one month following their submission to Retorno. 3. A semi-structured clinical interview 12-18 months following their submission to Retorno (~6-12 months following their discharge). A matched group of healthy controls completed the same DD task twice within a similar time interval.

Results: Behavioral results confirm that, as expected, drug addicts exhibit elevated impulsive behavior compared to healthy controls, expressed as higher likelihood to choose the immediate smaller reward over the larger delayed reward in the DD task (main effect of group F51 = 3.59, p = 0.06). Interestingly, DHEA selected dose completely abolished the impulsive behavior. Impulsivity could be imaged in the brain in real time engaged with the cognitive task. Analysis of fMRI data were focused on indices of decision making in multi-drug withdrawn patients, separately for impulsive “now choices” vs. non- impulsive future choices. Results reveal that both choices elicit robust activation in a single cluster located in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a core brain region for decision making. Comparing ACC activation between the groups reveled a trend towards higher activation in multidrug withdrawn patients that remained clean compared to those that relapsed (T7 = 1.44, p = 0.08). In other words, ACC activation during impulsive decision making predicted relapse risk 12-18 month later, such that higher activation was associated with increased likelihood to stay clean. DHEA in a selected manner can attenuate impulsivity that will lead a protection from relapse to drug usage.

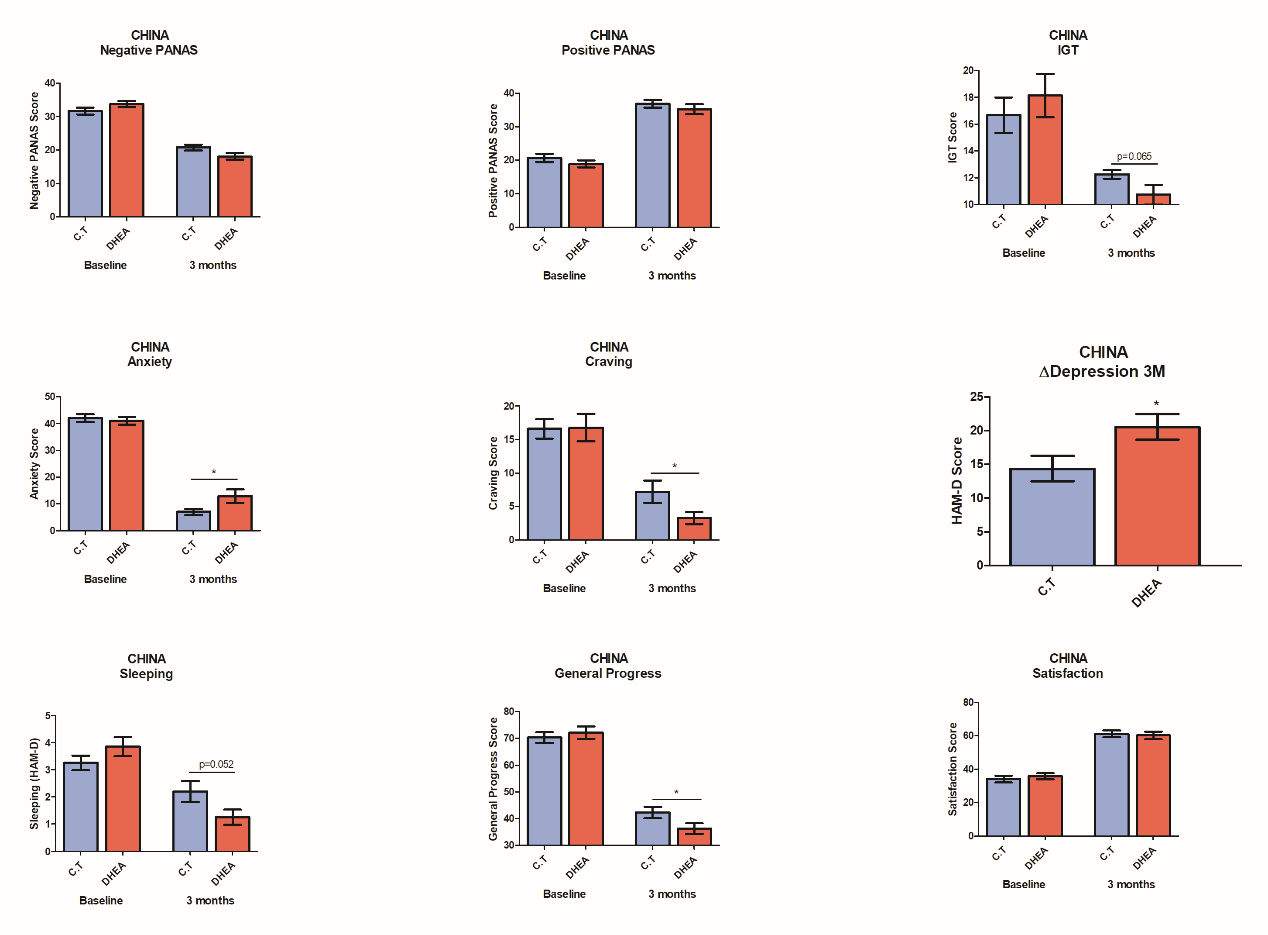

Clinical trial IV: Add-on DHEA treatment for Methadone therapy (China)

A clinical trial was conducted at the Gaoxin Hospital (Chaoyang District, Beijing, China), 40 male addicted patients aged 18-50, who were diagnosed according to the DSM-V for Substance Use, have been recruited and treated with either DHEA or Placebo pills for 3 months. Most patients participating in the trial didn’t undergo a prior detox process; instead they went through detox at the hospital. DHEA/Placebo was an add-on treatment to the regular hospital program (the patients received the following treatments: 20-50mg of Methadone, and complementary therapies (Tradition Chinese Medicine). It should be noted that patients received adjusted doses of DHEA after sampling their response to the initial dose at the first month. The adjustment was preformed according to our instructions based on the algorithm.

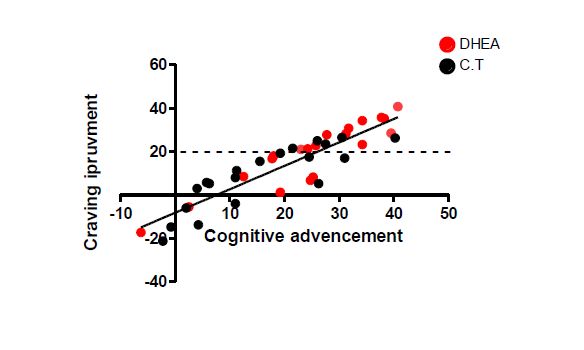

Our results showed a superiority of our program vs the ‘conventional’ treatment, in decision making, negative (PANAS) symptoms, general progress, depression, and sleep quality.

Moreover, our system could predict the long term beneficial effect of the treatment on craving. As, well we were able to see a significant improvement (p<0.02) in craving if the treatment was guided. Our data results were correlated with the Chinese questionnaires.

CONCLUSIONS

We suggest to use dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), a natural neurosteroid shown to prevent relapse to drug use in the long-term, as add-on treatment of addicts. DHEA add-on treatment may be seamlessly incorporated into existing rehabilitation programs, complementing and enriching the various therapies in each center and improving long-term abstinence rate.

Addiction is a complex disease with high relapse rates and no reliable treatment. We suggest introducing and promoting integrative treatment approach which is based on a unique combination of:

– Comprehensive physiological, psychological and cognitive tests

– Artificial Intelligence-enhanced algorithms for the establishment of individual programs

– Customized dosages of food supplements to balance out the patient’s hormonal profile . The unique algorithm takes into account the many aspects of this complicated disease and allows for dynamic assessment of the patient’s progress in a timely manner. ,We strongly believe that such a program may not only support, but boost rehabilitation process, and help millions of patients regain a normal life in a shorter amount of time.

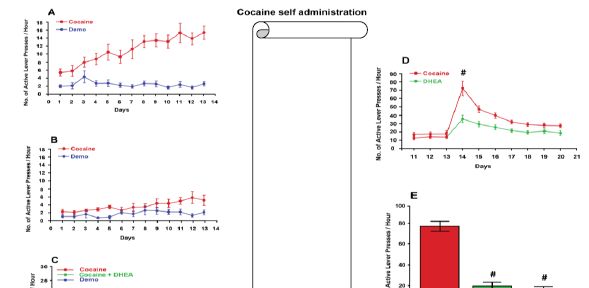

Figure 1: Effect of DHEA on cocaine seeking behavior and relapse- Preclinical experiments

Rats were operated and implanted with iv catheters. After 10 days of rehabilitation they were trained to self- administer cocaine (1 mg/ kg) in a FR-1 paradigm.

Panel A: An animal model for drug addiction: A typical progress of drug self-administration progress is depicted, from acquisition to maintenance, which is fully controlled by the animal.

Panel B: Effect of DHEA on cocaine acquisition. DHEA (2 mg/kg, B) was administrated prior consecutively 5 days before training and during training, 90 min before entering the rat into the self- administration chamber. Presses on the active-, non-active levers (demo) were recorded. A marked effect of DHEA pretreatment on drug seeking behavior was noticed (modified from Maayan et al., 2006).

Panel C: Effect of DHEA on cocaine maintenance. After rats reached stable maintenance (the figure indicate the three last days of maintenance before treatment; red symbols) and during DHEA (2 mg/kg) administration consecutively during maintenance (access to the drug intake was available), 90 min before entering the rat into the self- administration chamber. Presses on the active-, non-active (demo) levers were recorded. A longitudinal decrease in cocaine self- administration is depicted (modified from Doron, Fridman, Gispan-Herman, et al., 2006).

Panel D: Effect of DHEA on cocaine during drug extinction (washout). After rats maintained ten days of stable drug self- administration (the figure indicate the three last days of maintenance before treatment; red symbols), cocaine was extinct and DHEA (2 mg/kg) was injected, 90 min before entering the rat into the self-administration chamber. Presses on the active-, non- active (demo) levers were recorded. An immediate significant (# P<0.01) decrease in cocaine craving is depicted.

Panel E: Effect of DHEA on cocaine-priming induced reinstatement. Rats were treated with DHEA (2 mg/kg,) or saline consecutively during maintenance 90 min before entering the into the self- administration chamber, when the drug was available. After reaching the abstinence criterion (pressing <10% of maintenance), rats were reinstated with 10 mg cocaine i.v. and entered the chamber without accesses to cocaine. Craving was evaluated by measuring their presses on the active lever. As shown, relapse was abolished (# P<0.01) by DHEA treatment.

Figure 2: Effect of DHEA on cocaine seeking behavior and relapse-clinical trials

Treatment in a Detoxification center: DHEA effect, as a complementary treatment was evaluated in opiate addicts undergoing detoxification. DHEA (100mg/day) or placebo was added as a to the routine medication protocol in a randomized, double blind controlled study. Severity of withdrawal Symptoms (panel A), Depression (panel B) and Anxiety (panel C) scores were measured as a follow up for 12 months. #p<0.05 indicate statistically significant. HDRS: Hamilton depression scores, HARS: Hamilton anxiety scores (modified from Maayan et al., 2008).

Treatment in a rehabilitation center: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study examined the effect of DHEA in adult poly-drug users taking part in a detoxification program enriched with intensive psychosocial interventions and aftercare. During treatment, participants consumed DHEA (100 mg/day) or placebo daily for at least 30 days. While in treatment, DHEA significantly improved quality of life (QOL; Panel D), anxiety (Panel E) and release rates in a 16 months follow-up about a third compared to placebo (Panel F).

# P<0.01 indicate significance between treatment groups (modified from Maayan et al., 2008).

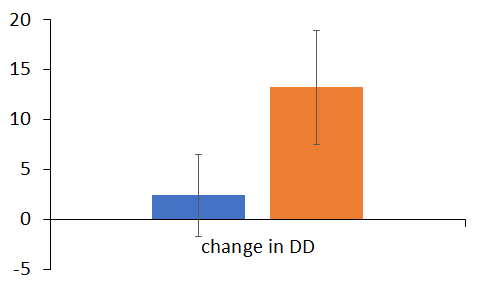

Clinical trial 3: Imaging cognitive effect of DHEA dose on impulsivity

A

B

Figure1 A. Comparing ACC activation between the groups reveled a trend towards higher activation in

multidrug withdrawn patients that remained clean compared to those that relapsed (T7 = 1.44, p = 0.08).

B.A change in impulsivity (before-after treatment of placebo (orange vs DHEA treated addicts)

Figure2 depicts the results of the fMRI data of these as choosing “future” (Figure2B) elicited distributed neural activations including in cortical, as well participants form the delay discounting task. Specifically, choosing “now”, as well as subcortical brain regions. These initial results correspond with previous findings in this task that demonstrated the extensive neural network that mediates decision making in the context of monetary reward. Notably, comparing neural response while choosing “now” vs. choosing “future” revealed bilateral activation in the ACC, indicating increased amygdala activation during impulsive behavior.

Clinical Trial IV: Effect of ADHA as add-on to Methadone (China)

References

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US), S. A. and M. H. S. A., & (US), O. of the S. G. (2016). Facing Addiction in America. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. US Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28252892

Aguilar, M. A., Rodríguez-Arias, M., & Miñarro, J. (2009). Neurobiological mechanisms of the reinstatement of drug-conditioned place preference. Brain Research Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.08.002

Anker, J. J., Holtz, N. A., Zlebnik, N., & Carroll, M. E. (2009). Effects of allopregnanolone on the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in male and female rats. Psychopharmacology, 203(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-008-1371-9

Aydar, E., Palmer, C. P., Klyachko, V. A., & Jackson, M. B. (2002). The sigma receptor as a ligand- regulated auxiliary potassium channel subunit. Neuron, 34(3), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00677-3

Baker, D. A., McFarland, K., Lake, R. W., Shen, H., Tang, X.-C., Toda, S., & Kalivas, P. W. (2003). Neuroadaptations in cystine-glutamate exchange underlie cocaine relapse. Nature Neuroscience, 6(7), 743–749. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1069

Ben-Ami, O., Kinor, N., Perelman, A., & Yadid, G. (2006). Dopamine-1 receptor agonist, but not cocaine, modulates sigma(1) gene expression in SVG cells. J Mol Neurosci, 29(2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1385/JMN:29:2:169

Bercik, P., Denou, E., Collins, J., Jackson, W., Lu, J., Jury, J., … Collins, S. M. (2011). The intestinal microbiota affect central levels of brain-derived neurotropic factor and behavior in mice. Gastroenterology, 141(2). https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.052

Brzoza, Z., Kasperska-Zajac, A., Badura-Brzoza, K., Matysiakiewicz, J., Hese, R. T., & Rogala, B. (2008). Decline in Dehydroepiandrosterone Sulfate Observed in Chronic Urticaria is Associated With Psychological Distress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 70(6), 723–728. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817bcc8d

Buchanan, J. (2006). Understanding Problematic Drug Use: A Medical Matter or a Social Issue? British Journal of Community Justice, 4(2), 387–397. Retrieved from http://epubs.glyndwr.ac.uk/siru

Burokas, A., Arboleya, S., Moloney, R. D., Peterson, V. L., Murphy, K., Clarke, G., … Cryan, J. F. (2016). Targeting the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: Prebiotics Have Anxiolytic and Antidepressant-like Effects and Reverse the Impact of Chronic Stress in Mice. Biological Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.12.031

Buydens-Branchey, L., Branchey, M., Hudson, J., & Dorota Majewska, M. (2002). Perturbations of plasma cortisol and DHEA-S following discontinuation of cocaine use in cocaine addicts. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 27(1–2), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-

4530(01)00037-3

Chao, J., & Nestler, E. J. (2004). Molecular neurobiology of drug addiction. Annu Rev Med, 55, 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.103730

Chen, Y., Hajipour, A. R., Sievert, M. K., Arbabian, M., & Ruoho, A. E. (2007). Characterization of the cocaine binding site on the sigma-1 receptor. Biochemistry, 46(11), 3532–3542. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi061727o

Colangelo, A. M., Alberghina, L., & Papa, M. (2014). Astrogliosis as a therapeutic target for neurodegenerative diseases. Neuroscience Letters, 565, 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2014.01.014

Di Chiara, G. (1999). Drug addiction as dopamine-dependent associative learning disorder. European Journal of Pharmacology, 375(1–3), 13–30. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10443561

Dikshtein, Y., Barnea, R., Kronfeld, N., Lax, E., Roth-Deri, I., Friedman, A., … Yadid, G. (2013). β- Endorphin via the Delta Opioid Receptor is a Major Factor in the Incubation of Cocaine Craving. Neuropsychopharmacology, 38(12), 2508–2514. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2013.155

Dong, L. Y., Cheng, Z. X., Fu, Y. M., Wang, Z. M., Zhu, Y. H., Sun, J. L., … Zheng, P. (2007).

Neurosteroid dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate enhances spontaneous glutamate release in rat prelimbic cortex through activation of dopamine D1 and sigma-1 receptor. Neuropharmacology, 52(3), 966–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.10.015

Doron, R., Fridman, L., Gispan-Herman, I., Maayan, R., Weizman, A., & Yadid, G. (2006). DHEA, a Neurosteroid, Decreases Cocaine Self-Administration and Reinstatement of Cocaine- Seeking Behavior in Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology, 31(10), 2231–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1301013

Doron, R., Fridman, L., & Yadid, G. (2006). Dopamine-2 receptors in the arcuate nucleus modulate cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuroreport, 17(15), 1633–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.wnr.0000234755.88560.c7

Dubrovsky, B. O. (2005). Steroids, neuroactive steroids and neurosteroids in psychopathology. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.001

Erb, S., Shaham, Y., & Stewart, J. (1998). The role of corticotropin-releasing factor and corticosterone in stress- and cocaine-induced relapse to cocaine seeking in rats. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 18(14), 5529–36. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9651233

Finn, P. R. (2002). Motivation, working memory, and decision making: a cognitive-motivational theory of personality vulnerability to alcoholism. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews, 1(3), 183–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534582302001003001

Geier, C., & Luna, B. (2009). The maturation of incentive processing and cognitive control.

Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2009.01.021 Genud, R., Merenlender, A., Gispan-Herman, I., Maayan, R., Weizman, A., & Yadid, G. (2009).

DHEA Lessens Depressive-Like Behavior via GABA-ergic Modulation of the Mesolimbic System. Neuropsychopharmacology, 34(3), 577–584. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2008.46 Goeders, N. E. (1997). A neuroendocrine role in cocaine reinforcement. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 22(4), 237–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-

4530(97)00027-9

Goeders, N. E. (2002). Stress and cocaine addiction. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 301(3), 785–789. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.301.3.785

Goeders, N. E. (2002). The HPA axis and cocaine reinforcement. Psychoneuroendocrinology. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(01)00034-8

Goeders, N. E., & Clampitt, D. M. (2002). Potential role for the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in the conditioned reinforcer-induced reinstatement of extinguished cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology, 161(3), 222–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-002-1007-4

Goeders, N. E., & Guerin, G. F. (1996). Effects of surgical and pharmacological adrenalectomy on the initiation and maintenance of intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats. Brain Res, 722(1–2), 145–52. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(96)00206-5

Guerin, G. F., Schmoutz, C. D., & Goeders, N. E. (2014). The extra-adrenal effects of metyrapone

and oxazepam on ongoing cocaine self-administration. Brain Research, 1575, 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2014.05.039

Haney, M. (2009). Self-administration of cocaine, cannabis and heroin in the human laboratory: Benefits and pitfalls. Addiction Biology. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00121.x

Harris, L.S. (Ed.), P. of D., & College. (1996). Relaps to cocaine use may be predicted in early abstinence by measures of dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate levels. Retrieved November 20, 2017, from https://scholar.google.co.il/scholar?cluster=9235639266510149232&hl=iw&as_sdt=2005 &sciodt=0,5

Hayashi, T., & Su, T.-P. (2003). Intracellular dynamics of sigma-1 receptors (sigma(1) binding sites) in NG108-15 cells. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 306(2), 726–33. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.103.051292

Hayashi, T., & Su, T. P. (2001). Regulating ankyrin dynamics: Roles of sigma-1 receptors.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 98(2), 491–

- https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.98.2.491

Hayashi, T., & Su, T. P. (2007). Sigma-1 Receptor Chaperones at the ER- Mitochondrion Interface Regulate Ca2+ Signaling and Cell Survival. Cell, 131(3), 596–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.036

Hiranita, T., Soto, P. L., Tanda, G., & Katz, J. L. (2010). Reinforcing effects of sigma-receptor agonists in rats trained to self-administer cocaine. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 332(2), 515–524. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.109.159236

Huerta-García, E., Montiél-Dávalos, A., Alfaro-Moreno, E., Gutiérrez-Iglesias, G., & López-Marure,

- (2013). Dehydroepiandrosterone protects endothelial cells against inflammatory events induced by urban particulate matter and titanium dioxide nanoparticles. BioMed Research International, 2013, 382058. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/382058

Jackson, A., Mead, A. N., Rocha, B. A., & Stephens, D. N. (1998). AMPA receptors and motivation for drug: effect of the selective antagonist NBQX on behavioural sensitization and on self- administration in mice. Behavioural Pharmacology, 9(5–6), 457–467.

Kalivas, P. W. (2009). The glutamate homeostasis hypothesis of addiction. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(8), 561–572. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2515

Kauer, J. A., & Malenka, R. C. (2007). Synaptic plasticity and addiction. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 8(11), 844–858. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2234

Kenny, P. J. (2014). Epigenetics, microRNA, and addiction. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 16(3), 335–44. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25364284

Kimonides, V. G., Khatibi, N. H., Svendsen, C. N., Sofroniew, M. V, & Herbert, J. (1998). Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA-sulfate (DHEAS) protect hippocampal neurons against excitatory amino acid-induced neurotoxicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 95(4), 1852–7. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.4.1852

Kiraly, D. D., Walker, D. M., Calipari, E. S., Labonte, B., Issler, O., Pena, C. J., … Nestler, E. J. (2016). Alterations of the Host Microbiome Affect Behavioral Responses to Cocaine. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 35455. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35455

Koob, G. F. (2009). Dynamics of Neuronal Circuits in Addiction: Reward, Antireward, and Emotional Memory. Pharmacopsychiatry, 42(S 01), S32–S41. https://doi.org/10.1055/s- 0029-1216356

Koob, G. F., Buck, C. L., Cohen, A., Edwards, S., Park, P. E., Schlosburg, J. E., … George, O. (2014). Addiction as a stress surfeit disorder. Neuropharmacology, 76, 370–382.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.05.024

Kwako, L. E., & Koob, G. F. (2017). Neuroclinical Framework for the Role of Stress in Addiction.

Chronic Stress, 1, 247054701769814. https://doi.org/10.1177/2470547017698140 L.Ulmann,J.-L.Rodeau,L.Danoux,J.-L.Contet-Audonneau,G.Pauly, R. S. (2009).

Dehydroepiandrosterone and neurotrophins favor axonal growth in a sensory neuron– keratinocyte coculture model. Neuroscience, 159(2), 514–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUROSCIENCE.2009.01.018

Levy, a D., Li, Q. a, Kerr, J. E., Rittenhouse, P. a, Milonas, G., Cabrera, T. M., … Van de Kar, L. D. (1991). Cocaine-induced elevation of plasma adrenocorticotropin hormone and corticosterone is mediated by serotonergic neurons. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 259(2), 495–500.

Liu, Y., & Matsumoto, R. R. (2008). Alterations in fos-related antigen 2 and sigma1 receptor gene and protein expression are associated with the development of cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization: time course and regional distribution studies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 327(1), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.108.141051

Lyte, M., Vulchanova, L., & Brown, D. R. (2011). Stress at the intestinal surface: Catecholamines and mucosa-bacteria interactions. Cell and Tissue Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-010-1050-0

Maayan, R., Lotan, S., Doron, R., Shabat-Simon, M., Gispan-Herman, I., Weizman, A., & Yadid, G. (2006). Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) attenuates cocaine-seeking behavior in the self- administration model in rats. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 16(5), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.10.002

Maayan, R., Morad, O., Dorfman, P., Overstreet, D. H., Weizman, A., & Yadid, G. (2005). The involvement of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and its sulfate ester (DHEAS) in blocking the therapeutic effect of electroconvulsive shocks in an animal model of depression. European Neuropsychopharmacology : The Journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 15(3), 253–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.10.005

Maayan, R., Touati-Werner, D., Shamir, D., Yadid, G., Friedman, A., Eisner, D., … Herman, I. (2008). The effect of DHEA complementary treatment on heroin addicts participating in a rehabilitation program: A preliminary study. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 18(6), 406–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.12.003

Majewska, M. D. (2002). HPA axis and stimulant dependence: An enigmatic relationship.

Psychoneuroendocrinology, 27(1–2), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(01)00033-

6

Mantsch, J. R., Baker, D. A., Serge, J. P., Hoks, M. A., Francis, D. M., & Katz, E. S. (2008). Surgical Adrenalectomy with Diurnal Corticosterone Replacement Slows Escalation and Prevents the Augmentation of Cocaine-Induced Reinstatement in Rats Self-Administering Cocaine Under Long-Access Conditions. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33(4), 814–826. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1301464

Martin-Soelch, C., Chevalley, A. F., Künig, G., Missimer, J., Magyar, S., Mino, A., Leenders, K. L. (2001). Changes in reward-induced brain activation in opiate addicts. European Journal of Neuroscience, 14(8), 1360–1368. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0953-816X.2001.01753.x

Massart, R., Barnea, R., Dikshtein, Y., Suderman, M., Meir, O., Hallett, M., … Yadid, G. (2015). Role of DNA methylation in the nucleus accumbens in incubation of cocaine craving. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 35(21), 8042–58. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3053-14.2015

Matsumoto, R. R., Liu, Y., Lerner, M., Howard, E. W., & Brackett, D. J. (2003). Sigma receptors: potential medications development target for anti-cocaine agents. European Journal of Pharmacology, 469(1–3), 1–12. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12782179

Maurice, T., Martin-Fardon, R., Romieu, P., & Matsumoto, R. R. (2002). Sigma1 (σ1) receptor antagonists represent a new strategy against cocaine addiction and toxicity. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7634(02)00017-9

Maurice, T., Phan, V. L., Urani, A., Kamei, H., Noda, Y., & Nabeshima, T. (1999). Neuroactive neurosteroids as endogenous effectors for the sigma1 (sigma1) receptor: pharmacological evidence and therapeutic opportunities. Japanese Journal of Pharmacology, 81(2), 125–155. https://doi.org/10.1254/jjp.81.125

McCollister, K., Yang, X., Sayed, B., French, M. T., Leff, J. A., & Schackman, B. R. (2017). Monetary conversion factors for economic evaluations of substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 81, 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2017.07.008

McLellan, A. T., Lewis, D. C., O’Brien, C. P., & Kleber, H. D. (2000). Drug Dependence, a Chronic Medical Illness. JAMA, 284(13), 1689. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.13.1689

McLellan, A. T., & Weisner, C. (1996). Achieving the Public Health and Safety Potential of Substance Abuse Treatments. In Drug Policy and Human Nature (pp. 127–154). Boston, MA: Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-3591-5_6

Mellon, S. H., & Griffin, L. D. (2002a). Neurosteroids: biochemistry and clinical significance. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism: TEM, 13(1), 35–43. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11750861

Mellon, S. H., & Griffin, L. D. (2002b). Synthesis, regulation, and function of neurosteroids. Endocrine Research, 28(4), 463. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12530649

Mendelson, J. H., Mello, N. K., Sholar, M. B., Siegel, A. J., Mutschler, N., & Halpern, J. (2002). Temporal concordance of cocaine effects on mood states and neuroendocrine hormones. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 27(1–2), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-

4530(01)00036-1

Miyatake, R., Furukawa, A., Matsushita, S., Higuchi, S., & Suwaki, H. (2004). Functional polymorphisms in the sigma1 receptor gene associated with alcoholism. Biol Psychiatry, 55(1), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.07.008

Moldow, R. L., & Fischman, A. J. (1987). Cocaine induced secretion of ACTH, beta-endorphin, and corticosterone. Peptides, 8(5), 819–822. https://doi.org/10.1016/0196-9781(87)90065-9

Mongi-Bragato, B., Zamponi, E., García-Keller, C., Assis, M. A., Virgolini, M. B., Mascó, D. H., … Cancela, L. M. (2016). Enkephalin is essential for the molecular and behavioral expression of cocaine sensitization. Addiction Biology, 21(2), 326–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.12200

Mucha, R. F., Van Der Kooy, D., O’Shaughnessy, M., & Bucenieks, P. (1982). Drug reinforcement studied by the use of place conditioning in rat. Brain Research, 243(1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(82)91123-4

Nachshoni, T., Ebert, T., Abramovitch, Y., Assael-Amir, M., Kotler, M., Maayan, R., … Strous, R. D. (2005). Improvement of extrapyramidal symptoms following dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) administration in antipsychotic treated schizophrenia patients: a randomized, double-blind placebo controlled trial. Schizophr Res, 79(2–3), 251–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.029

Nestler, E. J., & Malenka, R. C. (2004). The Addicted Brain. Scientific American, 290(3), 78–85.

https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0304-78

Nguyen, L., Lucke-Wold, B. P., Mookerjee, S. A., Cavendish, J. Z., Robson, M. J., Scandinaro, A. L., & Matsumoto, R. R. (2015). Role of sigma-1 receptors in neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences, 127(1), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphs.2014.12.005

Nie, H., & Janak, P. H. (2003). Comparison of reinstatement of ethanol- and sucrose-seeking by conditioned stimuli and priming injections of allopregnanolone after extinction in rats. Psychopharmacology, 168(1–2), 222–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-003-1468-0

Ohana, D., Maayan, R., Delayahu, Y., Roska, P., Ponizovsky, A. M., Weizman, A., Yechiam, E. (2016). Effect of dehydroepiandrosterone add-on therapy on mood, decision making and subsequent relapse of polydrug users. Addiction Biology, 21(4), 885–894. https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.12241

Panlilio, L. V., & Goldberg, S. R. (2007). Self-administration of drugs in animals and humans as a model and an investigative tool. Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360- 0443.2007.02011.x

Peters, J., Kalivas, P. W., & Quirk, G. J. (2009). Extinction circuits for fear and addiction overlap in prefrontal cortex. Learning & Memory, 16(5), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.1041309

Piazza, P. V., & Le Moal, M. (1998). The role of stress in drug self-administration. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-6147(97)01115-2

Piazza, P. V, Maccari, S., Deminiere, J. M., Le Moal, M., Mormede, P., & Simon, H. (1991). Corticosterone levels determine individual vulnerability to amphetamine self- administration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 88(6), 2088–2092. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.88.6.2088

Polter, A. M., & Kauer, J. A. (2014). Stress and VTA synapses: Implications for addiction and depression. European Journal of Neuroscience, 39(7), 1179–1188. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.12490

Reddy, D. S., & Kulkarni, S. K. (1997). Chronic neurosteroid treatment prevents the development of morphine tolerance and attenuates abstinence behavior in mice. European Journal of Pharmacology, 337(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2999(97)01294-6

Reddy, D. S., & Kulkarni, S. K. (1997). Reversal of benzodiazepine inverse agonist FG 7142-induced anxiety syndrome by neurosteroids in mice. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol, 19(10), 665– 681.

Reeves, R., Thiruchelvam, M., & Cory-Slechta, D. A. (2004). Expression of behavioral sensitization to the cocaine-like fungicide triadimefon is blocked by pretreatment with AMPA, NMDA and DA D1 receptor antagonists. Brain Research, 1008(2), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2004.01.079

Ren, X., Noda, Y., Mamiya, T., Nagai, T., & Nabeshima, T. (2004). A neuroactive steroid, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, prevents the development of morphine dependence and tolerance via c-fos expression linked to the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase. Behavioural Brain Research, 152(2), 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2003.10.013

Ritsner, M. S., Gibel, A., Ratner, Y., Tsinovoy, G., & Strous, R. D. (2006). Improvement of sustained attention and visual and movement skills, but not clinical symptoms, after dehydroepiandrosterone augmentation in schizophrenia: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 26, 495–499. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jcp.0000237942.50270.35

Romieu, P., Martin-Fardon, R., Bowen, W. D., & Maurice, T. (2003). Sigma 1 receptor-related

neuroactive steroids modulate cocaine-induced reward. J Neurosci, 23(9), 3572–3576. https://doi.org/23/9/3572 [pii]

Roth-Deri, I., Schindler, C. J., Yadid, G., I., R.-D., C.J., S., Roth-Deri, I., … Yadid, G. (2004). A critical role for beta-endorphin in cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuroreport, 15(3), 519–521. Retrieved from

http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med5&NEWS=N&AN=150 94515%5Cnhttp://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed6&NEWS

=N&AN=2004120123

Roth-Deri, I., Zangen, A., Aleli, M., Goelman, R. G., Pelled, G., Nakash, R., … Yadid, G. (2003a). Effect of experimenter-delivered and self-administered cocaine on extracellular beta- endorphin levels in the nucleus accumbens. Journal of Neurochemistry, 84(5), 930–8. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12603818

Roth-Deri, I., Zangen, A., Aleli, M., Goelman, R. G., Pelled, G., Nakash, R., … Yadid, G. (2003b). Effect of experimenter-delivered and self-administered cocaine on extracellular β- endorphin levels in the nucleus accumbens. Journal of Neurochemistry, 84(5), 930–938. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01584.x

Rupprecht, R., & Holsboer, F. (1999). Neuroactive steroids: Mechanisms of action and neuropsychopharmacological perspectives. Trends in Neurosciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-2236(99)01399-5

Saphier, D., Welch, J. E., Farrar, G. E., & Goeders, N. E. (1993). Effects of intracerebroventricular and intrahypothalamic cocaine administration on adrenocortical secretion. Neuroendocrinology, 57(1), 54–62.

Sarnyai, Z., Shaham, Y., & Heinrichs, S. C. (2001). The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in drug addiction. Pharmacol Rev, 53(2), 209–243. https://doi.org/10.2165/11587790-000000000-

00000

Self, D. W., & Choi, K. H. (2004). Extinction-induced neuroplasticity attenuates stress-induced cocaine seeking: A state-dependent learning hypothesis. Stress. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890400012677

Shah, A. H., Chin, E. H., Schmidt, K. L., & Soma, K. K. (2011). DHEA and estradiol levels in brain, gonads, adrenal glands, and plasma of developing male and female European starlings. Journal of Comparative Physiology A: Neuroethology, Sensory, Neural, and Behavioral Physiology, 197(10), 949–958. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00359-011-0655-4

Shaham, Y., Shalev, U., Lu, L., De Wit, H., & Stewart, J. (2003). The reinstatement model of drug relapse: History, methodology and major findings. Psychopharmacology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-002-1224-x

Shalev, U., Marinelli, M., Baumann, M. H., Piazza, P. V., & Shaham, Y. (2003). The role of corticosterone in food deprivation-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in the rat. Psychopharmacology, 168(1–2), 170–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-002-1200-5

Shoptaw S, Majewska MD, Wilkins J, Twitchell G, Yang X, L. W. (2004). Participants Receiving Dehydroepiandrosterone during Treatment for Cocaine Dependence Show High Rates of Cocaine Use in a Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 12(2), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1037/1064-1297.12.2.126\r2004-

13592-005 [pii]

Smith, A. C. W., & Kenny, P. J. (2017). MicroRNAs regulate synaptic plasticity underlying drug addiction. Genes, Brain and Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1111/gbb.12424

Stefanski, R., Justinova, Z., Hayashi, T., Takebayashi, M., Goldberg, S. R., & Su, T. P. (2004). Sigma1 receptor upregulation after chronic methamphetamine self-administration in rats: A study

with yoked controls. Psychopharmacology, 175(1), 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213- 004-1779-9

Stress psychobiology in the context of addiction medicine: from drugs of abuse to behavioral addictions. (2016), 223, 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/BS.PBR.2015.08.001

Su, T.-P., & Hayashi, T. (2003). Understanding the Molecular Mechanism of Sigma-1 Receptors: Towards A Hypothesis that Sigma-1 Receptors are Intracellular Amplifiers for Signal Transduction. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 10(20), 2073–2080. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867033456783

Sudai, E., Croitoru, O., Shaldubina, A., Abraham, L., Gispan, I., Flaumenhaft, Y., Yadid, G. (2011). High cocaine dosage decreases neurogenesis in the hippocampus and impairs working memory. Addiction Biology, 16(2), 251–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369- 1600.2010.00241.x

Sutton, M. A., Schmidt, E. F., Choi, K.-H., Schad, C. A., Whisler, K., Simmons, D., Self, D. W. (2003). Extinction-induced upregulation in AMPA receptors reduces cocaine-seeking behaviour. Nature, 421(6918), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01249

Tomkins, D. M., & Sellers, E. M. (2001). Addiction and the brain: the role of neurotransmitters in the cause and treatment of drug dependence. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal

= Journal de l’Association Medicale Canadienne, 164(6), 817–21. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11276551

Ujike, H., Kanzaki, A., Okumura, K., Akiyama, K., & Otsuki, S. (1992). Sigma antagonist BMY 14802 prevents methamphetamine-induced sensitization. Life Sciences, 50(16). https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3205(92)90466-3

Ujike, H., Kuroda, S., & Otsuki, S. (1996a). σ receptor antagonists block the development of sensitization to cocaine. European Journal of Pharmacology, 296(2), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2999(95)00693-1

Ujike, H., Kuroda, S., & Otsuki, S. (1996b). σ receptor antagonists block the development of sensitization to cocaine. European Journal of Pharmacology, 296(2), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2999(95)00693-1

Vescovi, P. P., Coiro, V., Volpi, R., & Passeri, M. (1992). Diurnal Variations in Plasma ACTH, Cortisol and Beta-Endorphin Levels in Cocaine Addicts. Hormone Research in Paediatrics, 37(6), 221– 224. https://doi.org/10.1159/000182316

Wang, Y. T. (2008). Probing the role of AMPAR endocytosis and long-term depression in behavioural sensitization: relevance to treatment of brain disorders, including drug addiction. British Journal of Pharmacology, 153 Suppl(July 2016), S389-95. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0707616

Wilkins, J. N., Majewska, M. D., Van Gorp, W., Li, S. H., Hinken, C., Plotkin, D., & Setoda, D. (2005). DHEAS and POMS measures identify cocaine dependence treatment outcome. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 30(1), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.04.006 Wolkowitz, O.M., Reus, V. I. (2003). Neurotransmitters, neurosteroids and neurotrophins: new models of the pathophysiology and treatment of depression. – PubMed – NCBI. Retrieved

November 20, 2017, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/12872201/ Wolkowitz, O. M., Kramer, J. H., Reus, V. I., Costa, M. M., Yaffe, K., Walton, P., Roberts, E. (2003).

DHEA treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurology, 60(7), 1071–1076. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/01.WNL.0000052994.54660.58

Wolkowitz, O. M., Reus, V. I., Keebler, A., Nelson, N., Friedland, M., Brizendine, L., & Roberts, E. (1999). Double-blind treatment of major depression with dehydroepiandrosterone.

American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(4), 646–649. https://doi.org/10200751

Wolkowitz, O. M., Reus, V. I., Roberts, E., Manfredi, F., Chan, T., Raum, W. J., Weingartner, H. (1997). Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) treatment of depression. Biological Psychiatry, 41(3), 311–8. https://doi.org/S0006322396000431

Yadid, G., Redlus, L., Barnea, R., & Doron, R. (2012). Modulation of mood States as a major factor in relapse to substance use. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 5, 81. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2012.00081

Yadid, G., Sudai, E., Maayan, R., Gispan, I., & Weizman, A. (2010). The role of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in drug-seeking behavior. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(2), 303–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.03.003

Yadid Gal, G., Sudai, E., Maayan, R., Gispan, I., & Weizman, A. (2010). The role of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in drug-seeking behavior. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.03.003